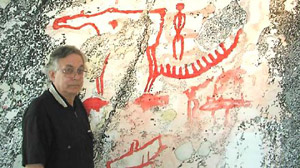

Picasso and grandson

Protean Picasso: Drawings and Prints from the National Gallery of Canada and Selected Paintings from International Collections, an exhibition that brings together the full scope of the artist’s career through drawings, prints and paintings, opened at the Vancouver Art Gallery on October 15, 2005 and will remain on display through January 15, 2006.

Most exciting news for Vancouver’s art mavens was that Picasso’s grandson Olivier Widmaier Picasso was in Vancouver last week for the opening. He also gave a talk at Robson Square about his biography Picasso: The Real Family Story, to counter books published by his cousins who’ve offered darker portrayals of their famous grandfather. Saturday’s (Oct.15th) Vancouver Sun has an interesting interview of Olivier Picasso, by Amy O’Brian. Because it may be not be available for long, I’ve copied it in full below.

In the shadow of Picasso

Living by Picasso or with Picasso is the question for a grandson

“You cannot escape from Picasso,” says the well-dressed man standing amid the Vancouver Art Gallery’s latest exhibition. “Even if you have a different name or if you want to hide the fact you are a grandson or relative of Picasso, once you’re discovered, it’s finished. People consider you as someone different.”

Olivier Widmaier Picasso, grandson of the famously fascinating Pablo Picasso, was in Vancouver this week for the opening of Protean Picasso at the VAG. He wandered around the dim galleries of the exhibition, pointing to portraits of his grandmother and talking — in a thick Parisian accent — about his distinguished and famous pedigree.

The 44-year-old’s grandfather is considered one of the greatest artistic minds of the 20th century, but has been portrayed on film and in papers as a womanizer and an irascible tyrant. Olivier has written a book in an effort to set the record straight on the legends surrounding his grandfather. “I didn’t want to find secrets,” he said. “I wanted to know if some of the legends were true, which was the case. Or were untrue, which was also the case in some situations.” Olivier is the product, one generation removed, of a 16-year love affair between Marie-Therese Walter and Picasso. The couple had one daughter, Maya, and Maya then had Olivier, Richard and Diana — three of the artist’s seven grandchildren.

During a brief tour of the VAG’s fall blockbuster show, Olivier stopped and pointed out a delicate portrait of a beautiful woman. With its finely drawn lines and careful shadowing, the portrait looks nothing like Picasso’s best-known cubist works, where his subjects are often fragmented and almost grotesquely portrayed.

The drawing is a perfectly proportioned likeness of Olivier’s grandmother. “She is the perfect image of a perfect muse,” he said while looking at the portrait. She was also blond and “very sexual,” Olivier said, while walking over to another drawing that portrays his grandmother’s likeness in four periods, ranging from neoclassical to cubist.

“[Pablo Picasso] was convinced that it was necessary for him to explore everything he could, not only on the artistic side but also on the human side,” Olivier said. “He was exploring a lot with different subjects, including different women.” Olivier doesn’t deny the legends about his grandfather’s passion for women, but believes he was a complicated man who was passionate about many things.

His book, ‘Picasso: The Real Family Story’, was written in an effort to accurately portray that man. Olivier never knew his grandfather, who died in 1973 when Olivier was still a boy, but he says his grandfather was so much a part of his universe that he felt compelled to find out the truth.

Growing up a Picasso or being connected to Picasso proved difficult for some, but Olivier says he was determined to embrace the challenges. “Either you live without Picasso, which is absolutely impossible, or you live by Picasso, thinking that everything is revolving around him and your life is revolving around him and you become a victim, because you’re losing yourself,” he said. “Or you live with Picasso, and I think that’s the best way to accept that 10 to 15 per cent of your life will always be influenced by him.”

Another of Picasso’s grandsons, named Pablo after the artist, killed himself shortly after Picasso’s death. “He drank bleach and he didn’t die immediately. He died after three months.”

Olivier said it was simply too complicated to carry the burden of a name that was known in nearly every household. “Imagine in the 1950s, going to school and kids saying ‘What is your name?’ ‘My name is Pablo Picasso.’ It was like being called Charles De Gaulle. It was impossible to survive,” he said. “The son of a banker can be a banker, but the son of Picasso is not Picasso.”

Olivier’s grandmother and Picasso’s second wife also committed suicide after the artist’s death. “Those two women had probably lost their extraordinary link to Picasso. When he died, they [returned] to the ordinary life,” he said. “There was no more excitement. They both probably felt it was better to try to find him again somewhere than to survive in that situation.”

Peer into the complicated mind of Pablo Picasso at the VAG until January 15.